It’s unfolding once more. Mali, the stage for a decade-long United Nations peacekeeping mission, MINUSMA, is bracing for a significant shift. On Friday, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) cast a unanimous vote to terminate MINUSMA’s operations. The resolution, drafted by France, mandates MINUSMA to systematically transfer its tasks and organise a secure, orderly withdrawal of its personnel by the close of 2023. The day after the resolution, on the 1st of July, the order was brought into effect.

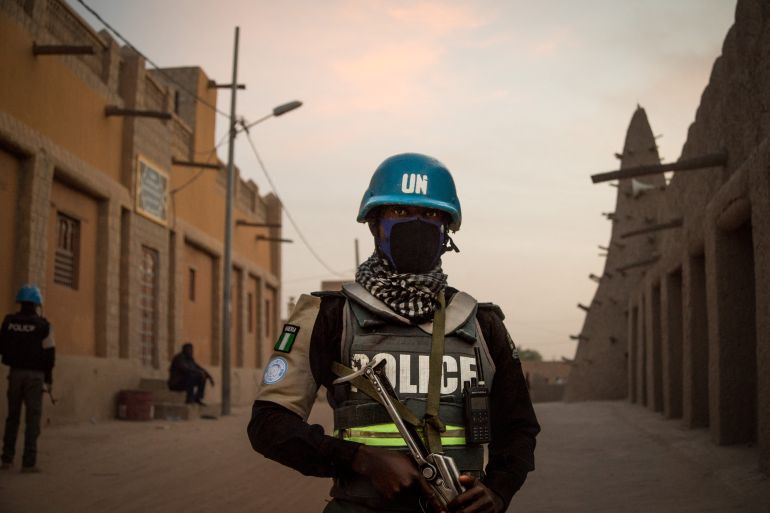

Why does history seemingly enjoy repetitions of precarious turns? We collectively marvelled at the tenacity of MINUSMA, a peacekeeping force of 13,000, tackling insecurity in Mali for over ten years. And now, Mali’s military junta has demanded its abrupt departure. The junta’s call was announced by Mali’s Foreign Minister, Abdoulaye Diop, prompting the US State Department to express grave concerns over potential impacts on Mali’s security and humanitarian situation. Yet despite these apprehensions, a six-month grace period for the peacekeepers’ exit has been granted by the UN.

The tale echoes familiar refrains. Instances when political manoeuvring results in the potential compromise of stability and peace. Mali’s military leaders have persistently regarded the UN and Western presence as an intrusion. This sentiment is rising amidst the nation’s ongoing fight against an Islamist insurgency, a torment which took root post the 2012 uprising, spreading to the broader Sahel region, to Niger, Burkina Faso, and of late, northern Côte d’Ivoire.

Back in 2013, MINUSMA was deployed by the UNSC to reinforce local and foreign efforts to regain stability. Yet, the relentless insecurity led to two coups in 2020 and 2021. In response, the Mali junta partnered with Russia’s Wagner mercenary group in 2021. This alliance, built on shared goals and interests, brings an intriguing dynamic into Mali’s security dilemma.

The International Crisis Group, last Friday, cautioned that the removal of UN forces might further destabilise an already fragile security scenario. It underscored the loss of 187 peacekeepers over the mission’s span. But this casualty count is not the prime catalyst for the UN’s exit; Mali’s military regime remains firm on its stance for an international forces’ withdrawal, regardless of the severe security crisis.

In the absence of UN peacekeepers, the country will lean heavily on the Russian Wagner group, rumoured to have a 1,000-strong force in the country. Despite Wagner’s notorious reputation, concerns arise over its effectiveness in countering the jihadists who continue their assaults across the northern and central regions of Mali.

The deepening Russian foothold could be a strategic jab against France and the US, escalating its clout in West Africa. However, a recent fallout between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Yevgeny Prigozhin, the leader of the Wagner group, could potentially muddle this arrangement.

The UN’s exit could lead to a worsening humanitarian crisis, particularly in the north-east, where thousands of civilian villagers have sought refuge in camps encircling the small desert town of Ménaka. It is these vulnerable communities that stand to suffer most from the UN mission’s departure.

The exodus of UN forces from Mali, signalling the end of a ten-year peacekeeping mission, underscores the intricate and volatile political-security matrix in West Africa. The decision to discontinue the mission flags a considerable pivot in international strategy, igniting concerns about the future of security and stability in the region. “Never again” echoes ominously in this context, yet, we can only hold our breath and wait.

Image Credit: Florent Vergnes/AFP